I spend a lot of my time thinking about ‘femininity’. My work on the first history of women in corporate leadership requires that I discuss the assumed, and actual, wants and needs of corporate women. I examine the way women are expected to act, how they actually act, and what they and other people think about the way they act. So much of the academic literature, industry commentary, and personal anecdotes are similarly hyper-fixated on the way women think and act. Of course, there are multiple ways to be a woman, and this may or may not overlap with one of a myriad possible expressions of femininity. But, because corporate women operate in the world in the year of our lord 2025, they are constantly performing for, and against, broader social and cultural expectations of their femininity. To conform with what is expected, unfortunately, reinforces gender stereotypes, and to rebel against these is to invite questions, and risk judgement and ostracization. It sounds exhausting, because it is.

I spend far less time thinking about masculinity. Importantly, the very toxic parts of masculinity are often discussed, but we know less about the everyday stories that guide how men see themselves in the world. In corporate leadership particularly, masculinity is usually rendered invisible as the default mode of operation. It silently guides the corporate practices that determine who gets paid, promoted and rewarded, and yet many consider it a ‘neutral’ baseline rather than a culture that advantages some, and disadvantages others. As a result, men (and/or those who perform masculinity) are considered part of the very fabric of corporate management, whereas women (and/or those who perform femininity) are considered disrupters to corporate work who must be accommodated. Corporations are thus conceptualised as gender neutral; women are the sole ‘havers’ of gender; and gender conflict and inequality are introduced when women enter. Although rarely phrased in this way, the implication is usually something along the lines of: “everything was fine until you gals came in and made a fuss”.

I have recently been working on remedying this – in a small way – by examining Australia’s mid-century company men. The 1950s, 1960s and 1970s are a really important moment in the history of Australian managerial capitalism. In the aftermath of the Great Depression and Second World War, the post-War decades were characterised by optimism, full employment, technological innovation and the centring of a middle-class suburban existence. A ‘modern’ managerial class replaced the earlier entrepreneurial capitalism in which owners managed and managers owned. Women were relieved of their wartime duties, and were encouraged to focus on their domain of the home. Men, on the other hand, were tasked as breadwinners, aspiring to a stable middle-class professional career with a single employer. Throughout the twentieth century, these ‘company men’ became central to the new internal management and executive structures of large industrial companies.

Mid-century executive management was gendered not only by employing men, but by reproducing a hegemonic version of Australian masculinity. Executive management was delineated along traditional lines between husband and wife, and the public and private sphere. First, managers saw themselves as the ultimate breadwinner, and their success was defined by mastery of, and dedication to, their job. Company men worked hard, often at the expense of their relationships and health, in jobs that were directly connected to the masculine physicality and practicality of the industrial economy. Company men were nationalists, and capitalists, and re-asserted military masculinity through a Napoleonic control over company operations. Second, success at work meant company men were expected to work as if they were totally unencumbered by family care or household responsibilities. They worked long hours, travelled frequently, and were often relocated for internal promotions. This, in practical terms, required the division of labour with a wife. Marriage was necessary: society considered single men immature or, god forbid, homosexual, and divorced men offensive to middle-class sensibilities. Upwardly mobile men selected their spouse very carefully, and their wives contributed the diverse domestic, emotional and social labour necessary to maintain their family’s social and professional standing.

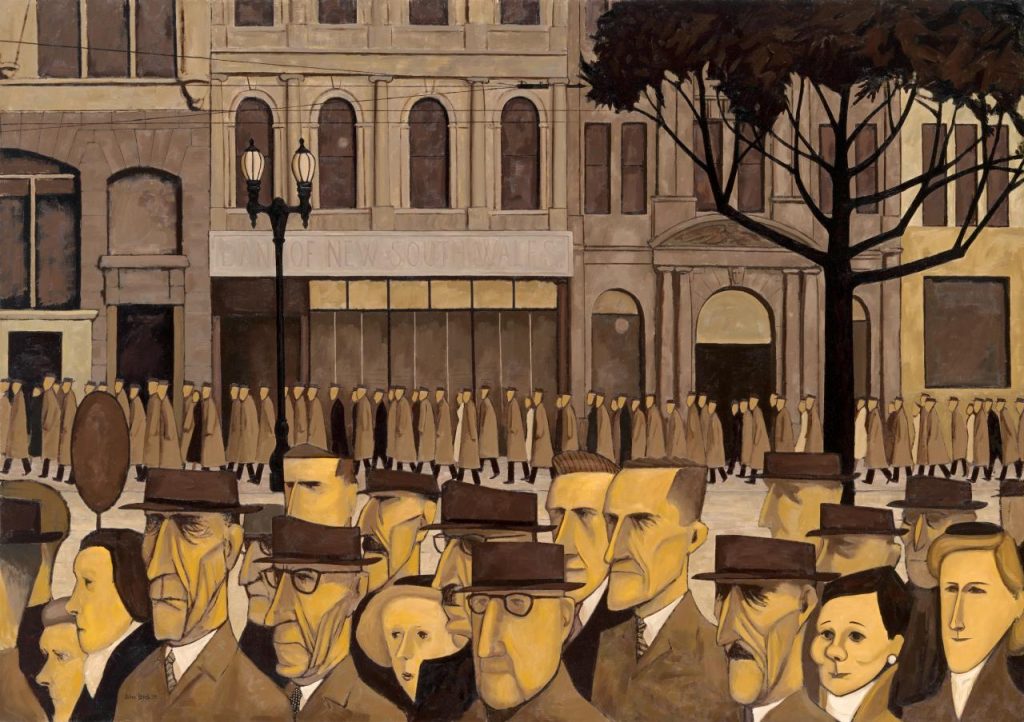

From the National Gallery of Victoria. In the early 1950s John Brack painted ‘Collins St, 5p.m.’ “Here, the artist depicts Melbourne’s financial hub at the end of the working day, its uniformly dressed office workers streaming homeward. Inspired by Brack’s own experience working for a city-based insurance company, the formal repetition and muted palette enhances the overarching sense of drudgery of nine-to-five office life”.

From the 1980s, various institutional shocks – including the transition to a post-industrial economy, globalisation, democratisation of shareholding and government free-market reforms – changed the work of Australian management. Older post-War theories of organisations were cast aside in favour of neoliberalism, which dispensed with professionals’ claim to moral authority (see Hannah Forsyth’s work on this!) and instead argued that success, as determined by the market, was the only virtue that really mattered. Companies increased the number of executives and standardised their responsibilities, with a typical executive suite by the 1980s consisting of up to a dozen managers. CEOs were increasingly appointed from outside the company, and executive leadership became a profession onto itself, rather than an extension of operational expertise.

Although company men no longer dominated Australian corporate boardrooms, executive work continued to reflect the mid-century divisions between breadwinners and housewives, and the public and private spheres. From the 1970s, women comprised a growing proportion of the corporate labour force, though employers typecast them in positions that aligned with assumptions of their natural domesticity (such as HR, marketing, law and public relations). At home, women’s hard-won career opportunities came with little change in the division of labour in households. Women were considered the ‘natural’ carer within nuclear families, and many embraced the ‘career family juggle’. This presumed breadwinning from husbands (and exonerated them from domestic responsibilities), while wives were now expected to optimise between “cramming a week’s work into three or four days”, and managing housework and childcare.

Uncovering masculinity in corporate management feels very close to stating the obvious. Corporate management, as any other job, carries the image of its ideal occupant, and the marginalisation of women – and indeed any other minority – owes much to the way Australian management was gendered in the mid-twentieth century. Many of these values and expectations are so embedded in the way we work, that we seldom take the time to stop and examine where they come from (and, of course, if they still serve us!). I hope this work can help us interrogate the cultural and material barriers that women and other minorities still face, and re-shape them with a focus on justice and equality.